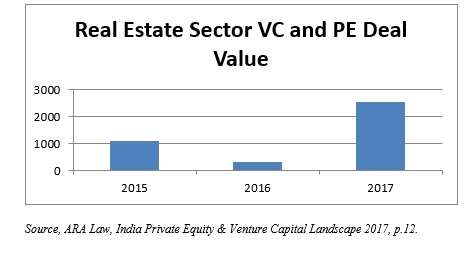

ARA Law, a firm based in Mumbai and Bangalore, India, has issued a paper on private equity and venture capital in that country. In a foreword, firm founder Rajesh N. Begur observes that there is a positive dynamic now at work in India’s economy, one that in his view “can be attributed to the structural and fundamental policy reforms instituted this year, as well as to the hangover of some reforms instituted in 2016.” One example of the 2017 wave of reforms is the Goods and Services Tax bill (the GST) passed in parliament on March 29, 2017. It creates a single centralized and rationalized tax system that has replaced the preceding confusing and sometimes conflicting patchwork of taxes. GST has already helped strengthen investor faith in India as a country where it makes sense to do business. The main text of the paper begins with sectoral analysis and market behavior. PE and VC investments in India declined in the early months of 2017, but they had started to pick up already before the end of the first quarter and in the third quarter investments by such vehicles “surprised the market with a tremendous jump in deal volume as well as value.” In August of that year the deal value reached US$5 billion. The third quarter as a whole saw 129 deals of value greater than US$100 million, aggregating to about US$7 billion. Final Numbers and Series B ARA says that although final numbers for 4Q “are not yet available, our independent reports suggest that it is in all likelihood going to showcase a performance similar to Q3. We cannot be more elated!” On a somewhat cautionary note, the report also says that there has been difficulty for those trying to raise Series B rounds, as when the initial projections made during the first funding rounds have disappointed. A number of players believe that Series B rounds have become tricky because investors have adopted a “lower tolerance level.” The most lucrative sector last year was e-Commerce, “in spite of the sharp fall in investments by the end of AY 2016,” followed by real estate. In the 3d quarter, e-Commerce recorded roughly US$2.6 billion in deals across 18 deals. Real estate? US$2.3 billion across 13 deals. Banking and Financial Services? Third place in the league table with US $1.4 billion across 25 deals. In both the e-Commerce and the real estate sectors there was a sharp diminution from 2015 to 2016, and then an exuberant rebound in 2017. In the case of real estate the rebound (shown in US$ millions) is graphed below.  The report also discusses India’s judiciary, and the part it has played in making the country friendlier to investors in recent years and months. It cites for example the decision by the Delhi High Court in Cruz City Mauritius Holdings v. Unitech Limited. This decision upheld the enforcement of a foreign arbitral award in India, and in the process touched upon “the critical issues of judicial treatment of restrictions imposed by Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on foreign investors.” One take away from Cruz City is that “RBI restrictions on exit at an assured return [are] not a blanket restriction.” The paper also cites I-Max v. E-City, a decision of India’s Supreme Court likewise favorable to foreign arbitral awards and the enforcement of their consequences in India. In this case the choice of arbitral seat (of London in the matter before the court) was “upheld as a valid and binding choice.” Start-Ups and Convertibles The paper also contains a careful discussion of the Start-Up Action Plan introduced by the government of India in January 2016, which includes “several tax exemptions, regulatory and compliance relaxations for Start-ups.” The plan also provided for the issuance by start-ups of convertible notes. That last bit was something of a novelty. Convertible notes for seed funding, common in the U.S., have not until now had a legal back-stop in India, and ARA expects that this aspect of the Start-Up Action Plan “will act as a major boost to Start-up funding by providing another venue for Start-Ups to raise money.” Finally (for our precis anyway) the paper looks at corporate governance issues in India and it suggests that India has been too wedded to the Anglo-Saxon model, which is designed mainly to reconcile conflicts between directors and shareholders. This model, ARA says, “is inherently designed at taming the over-powered Boards in the West.” That is not the problem India’s corporations and its investing environment face, and not the solution to the problems that they do face instead.

The report also discusses India’s judiciary, and the part it has played in making the country friendlier to investors in recent years and months. It cites for example the decision by the Delhi High Court in Cruz City Mauritius Holdings v. Unitech Limited. This decision upheld the enforcement of a foreign arbitral award in India, and in the process touched upon “the critical issues of judicial treatment of restrictions imposed by Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on foreign investors.” One take away from Cruz City is that “RBI restrictions on exit at an assured return [are] not a blanket restriction.” The paper also cites I-Max v. E-City, a decision of India’s Supreme Court likewise favorable to foreign arbitral awards and the enforcement of their consequences in India. In this case the choice of arbitral seat (of London in the matter before the court) was “upheld as a valid and binding choice.” Start-Ups and Convertibles The paper also contains a careful discussion of the Start-Up Action Plan introduced by the government of India in January 2016, which includes “several tax exemptions, regulatory and compliance relaxations for Start-ups.” The plan also provided for the issuance by start-ups of convertible notes. That last bit was something of a novelty. Convertible notes for seed funding, common in the U.S., have not until now had a legal back-stop in India, and ARA expects that this aspect of the Start-Up Action Plan “will act as a major boost to Start-up funding by providing another venue for Start-Ups to raise money.” Finally (for our precis anyway) the paper looks at corporate governance issues in India and it suggests that India has been too wedded to the Anglo-Saxon model, which is designed mainly to reconcile conflicts between directors and shareholders. This model, ARA says, “is inherently designed at taming the over-powered Boards in the West.” That is not the problem India’s corporations and its investing environment face, and not the solution to the problems that they do face instead.