Goldman Sachs threw in the towel two years ago. Well, “a towel,” anyway. Goldman has lots of towels. But two years ago, Goldman gave up on market making at the US options exchanges. In time for the anniversary, Alphacution has posted a research paper on the “long arc” of options market making at Goldman Sachs. The paper’s bottom line is that Goldman never learned to make good use of the assets it acquired when it bought Hull Trading Company from founder Blair Hull in 1999.

The author, Paul Rowady, says that this is something firms generally don’t confess when they exit part of a market. That is, “[S]omeone else has been eating their lunch and they haven’t been able to figure out how to justify the costs of adequately combating that competitive threat.”

Rowady, Alphacution’s director of research, refers to “the mighty Goldman Sachs,” and describes it as one of the “kings of Wall Street.” Goldman bought Hull Trading about 20 years after Blair Hull had first invented an empirical options trading model that derived its results independently of the Black-Scholes model, setting the stage for the creation of the company that would bear his name.

That is an important point. The Black-Scholes theorem (as Black, Scholes, and Merton perfectly understood) makes idealizing assumptions, so it can be wrong. Since it can be wrong, it can be bettered, and since by the time Hull was getting to work on this issue, Black-Scholes was firmly built into options pricing, anyone who could better its outputs could gain a lot of alpha.

By the fourth quarter of 2004, Goldman had integrated Hull Trading with another of its acquisitions, Spear, Leeds, and Kellogg (SLK), a New York-based securities clearing operation. SLK/Hill was a single unit for reporting purposes.

Scaling Up and Sloppy Reporting

By late 2006, Goldman began scaling up the operations of this unit. As Rowaday says, this suggests that until then it had been working out what it considered to be kinks in the engine, and it was now ready to press down on the accelerator.

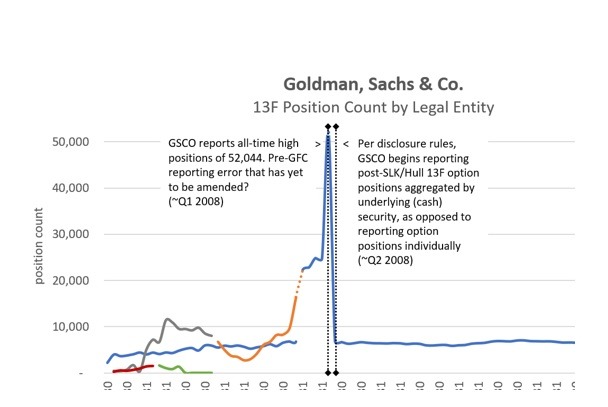

The graphic above, from Alphacution’s report, shows the Securities and Exchange Commission 13F position count for Goldman’s broker-dealer operations broken down by the legal entities that did the broking or the dealing.

Note that the chart shows a big upward jump between the 4th quarter of 2017 and the 1st quarter of 2018, from close to 25,000 positions to 50,000. Rowady suggests that this was the result of a reporting error that has never been corrected.

The immediate sharp decline in positions reported after that peak came about through changes in reporting rules, but it would have been a good deal less dramatic had the artificial upsurge from 2017 to 1Q 2018 not preceded it.

That spike, both up and down, illustrates a more general point. Goldman isn’t alone in the derivatives space in sloppy reporting. Rowady says that “a full spectrum of trading firms who are presumably supposed to bear the full weight of 13F disclosure requirements have incomplete and/or erroneous filing archives…. What’s the purpose of these regulations again? And, who is monitoring this data, but a few analysts like us?”

Lingering and Dying

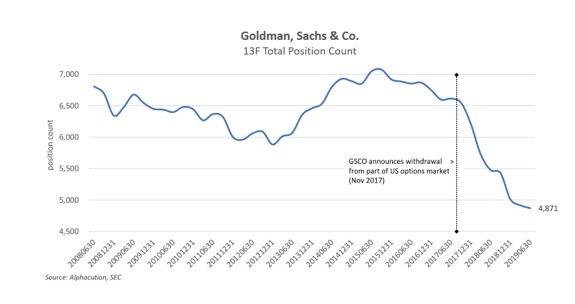

Moving forward, we come to Alphacution’s presentation of the 13F total count position over the 45-quarter period from Q2 2008 to Q2 2019. This graph from the Alphacution report takes the data from the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The necessary takeaway here is that the high comes in the third quarter of 2015, with a steady decline thereafter. Goldman’s decision to withdraw from a critical part of the market, and the consequences of that decision, shows up as the vertical line through the above chart, and the quick fall-off thereafter.

Now that Goldman has surrendered, what are the competitive advantages of the successful firms that remain in this market-making business that allow them to triumph over mighty Goldman Sachs, a Goldman fortified by the work of a Blair Hull?

Rowady says the successful firms do have technological advantages and very talented people, but they also acquire success as market makers from “trading in a wide range of securities that are linked to the underlying securities, like ETFs and options.” The winners have a combination of scale and niche right. They have the ability to price spreads across product classes, letting them bleed less well-connected latecomers into submission.