By Aaron Filbeck, CAIA, CFA, CIPM – Associate Director of Content Development at CAIA Association

In the title reference, the character Dr. Emmett Brown says this about a bolt of lightning: “Unfortunately, you never know when or where it is ever gonna strike.”

Frame of reference is everything when it comes to investing. Whether it’s the time period in which we entered the industry, when we decided to look at our quarterly statements (tip: wait until next quarter), or when we first learned the fundamentals of investing, our frame of reference can have a significant impact on how we approach putting investing dollars to work. We must challenge ourselves to broaden our perspectives to mitigate these biases, which can sometimes be so painful that we all want to make like a tree and “get out of here.”

The Trouble with Performance

We have written extensively about some of the inherent issues of using indexes as proxies for alternative investments. Whether these indexes are not investible, are subject to survivorship and backfill bias, ignore dispersion, or potentially understate volatility due to sub-manager diversification, there are a lot of arguments against using indexes to measure alternative investments performance.

In the spirit of contradicting myself, I’m still going to use these indexes in this piece. “Great Scott!” you say? Why? Despite all their flaws, they’re still one of the best ways we have to measure performance . This time, however, I want to talk about the influence of past performance on our frame of reference.

Time and time again, we’ve been told that “past performance is no indication of future results.” Yet, it’s so tempting to look at past performance and make knee-jerk decisions solely from those statistics, even if those statistics tell us nothing about the future. At the manager selection level, we’ve seen that investors are prone to fire an underperforming manager and hire an outperforming manager. At the asset class level, we see the same thing but perhaps the consequences are deadlier.

The Temptations of an Allocator

“I’m your density. I mean, your destiny.”

As allocators (or as a former one in my case), we are all subject to the temptation of performance chasing at the asset class level too. Imagine being a first-time investor in 2020 looking at a 10-year return for most asset classes. It might be tempting to put 100% of your capital in global stocks. Even if you’re not new to investing, it’s still tempting.

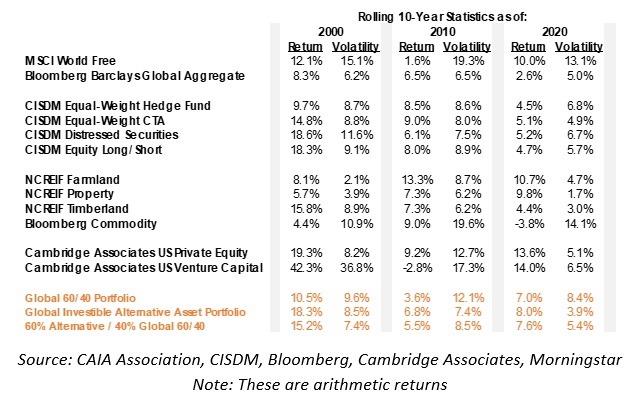

The table below shows the rolling 10-year return and volatility statistics for each of the asset classes, as well as those for a global 60/40 portfolio, the global investible alternative investments portfolio (GIAA), and our endowment-like portfolio of 60% GIAA and 40% in a 60/40.

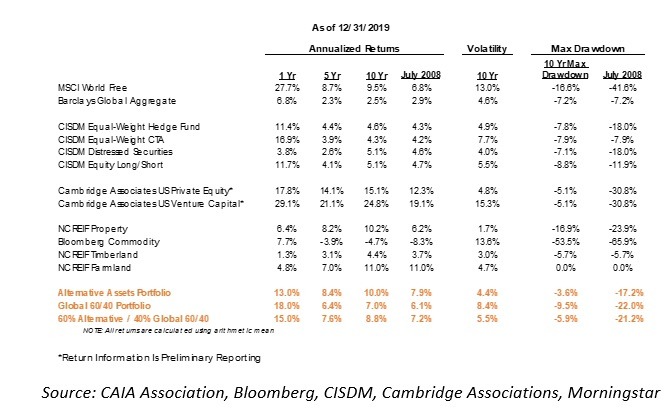

Typically, we show these statistics as of the most updated quarter and show a rolling 1-, 5-, and 10-year return, volatility, and max drawdown. More recently, we added a column that shows performance starting from mid-2008, since the GFC is no longer captured in the 10-year return. Notice the max drawdown for global stocks goes from -16% to 41%. This raises the question – what if I was looking at this same table at a different point in time?

Going Back in Time

To illustrate my point, let’s take the same list, but show what an investor would have observed in 2000, 2010, and 2020. Some of you reading this piece have already lived this, but for those who have not, let’s hop in the DeLorean and piece together an investment journey of our own. You’re about to see some crazy sh… stuff.

Ignoring what we know now, let’s try to put ourselves in the shoes of an investor in all three of these time periods. How tempting would it be to chase performance?

- 1990s: It’s 2000, you’re still in the midst of the tech boom. Venture capital has compounded 42% per year for 10-years in 1990s, fueled by the technology boom. This is never going to end, party like it’s 1999! You’re asking yourself, “we’re in a new regime, why would I even think of owning anything else besides tech?”

- 2000s: It’s 2010, we just finished a decade with two massive equity drawdowns, they’re calling it the “lost decade” for equity investors. You’re asking yourself, “why do I own equities at all? I should have put all my money in alternatives! Hedge funds are sexy!”

- 2010s: It’s 2020, you’re putting together your quarterly statement and notice that if you had just invested 100% in public equities, you could have called it a day. You’re asking yourself “why do I own bonds or these alternatives at all?” (Nice return you got there… it’d be a shame if anything were to happen to it in a few months.)

Of course, we already know what happened after 2000 and 2010. After dominating markets in the 1990s, we know (on average) venture capital lost money on an annualized basis in the 2000s. After performing extremely well in the 2000s, we know that hedge funds struggled on a relative basis to long-only equities in the 2010s.

The Shifting Value Proposition

In the 1990s, alternative investments trounced public markets, almost doubling its return with similar risk. In the 2000s, alternatives still outperformed global equity markets, but with almost half the risk. In the 2010s, alternatives provided similar returns, but with far less risk. What will the next decade bring? Maybe you aren’t ready for that yet, but your kids are gonna love it.

Not every asset will consistently outperform the rest of the portfolio, but if we use history as a guide, having exposures to multiple risk premia can increase the probability of meeting objectives, lower portfolio volatility, and provide shallower drawdowns.

It’s always fun to play the guessing game and it will be even more interesting to look at those rolling returns as of 12/31/2029. Unfortunately, we don’t have the proverbial almanac that gives us all the answers ahead of time to know if indeed that “bolt of lightning will strike the clock tower at precisely 10:04 PM, next Saturday night!” Let’s be smart about this and admit that we don’t know what we don’t know.

Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM is Associate Director, Content Development at CAIA Association. You can follow him on Twitter and LinkedIn.