Lydia Ofori, CFA, CAIA

Chief Executive Officer at Victoria Lion Partners

Private assets have come of age, in part thanks to an over stretched liquid market which has led to little or no room for alpha generation, and also due to a growing familiarity of the concept of private ownership in institutional portfolios. In today’s market environment, where a point yield advantage could have tremendous impact on one’s portfolio, the searches for deals and investment teams who can effectively execute are pursued with great rigour.

The argument regarding the benefits of investing in private markets is well debated, but not necessarily the focus of our discussions in this article. Studies that compare long term returns of private assets to public markets support the premise that private assets strategies add value to an overall portfolio (of course dependent on vintage, strategy, region, etc.) [1]. Other research [2 and 3] shows that individuals have more explanatory power in private capital funds (particularly VCs). Additional evidence [4] lends the same argument to buyout funds.

There’s a common trend in the industry where individuals leave large organizations to launch their own firms, often classified as ‘Emerging Managers’ [5]. There are some factors that the industry assigns to these managers, such as fund iteration (Fund I, II etc), fund size and capital deployed under the new banner (e.g., below $2bn deployed under the new firm banner), or the level of diversity amongt the founding team. If it is indeed individuals that influence private equity performance, then perhaps emerging managers should be considered, as they could be great sources of differentiated deal flow and alpha for institutional investors.

Broadly speaking, emerging managers in private assets could be likened to small caps in public equities markets (although we usually compare private markets in general to liquid market small caps). Similar to emerging managers, small caps in public market equities are usually under-researched names with little or no sell side research coverage, a potentially attractive to a buy side analyst who commits her time to uncover information uncovered by few - and thus - a potential source of alpha. Although there is little descriptive crossover of a small cap public stock to a private asset emerging manager, there are similarities in the fundamental driving objective of the small cap buy side analyst and that of the private asset emerging manager. Both have a propensity to identify that which is not entirely visible to their peers.

The common mistake that one makes is to place too much attention on the fund family of the individual. The emerging manager is not so different from her peers in terms of network access or experience. She has the same level - or better - access to networks and relationships to identify opportunities, and the same or better capabilities to execute that said strategy. In my opinion, perhaps an emerging manager’s ability and propensity to perform better than larger firms may come from focus. I categorize focus into two main areas: focus on a speciality or sector, and focus originating from the individual’s psyche.

• Speciality: We find that most emerging managers have a sector and/or investment style specialty – for example healthcare, technology, media, cybersecurity, logistics, etc. (sectors); small to lower mid-market (size), US focused, UK, Iberia (country, region specific). Emerging managers tend to find the gaps within a broader market set where they have the most networks (a common factor amongst all private assets investors) and where they can execute nimbly and generate oversized returns by putting sizeable yet relatively smaller capital to work. Evidential work from Cambridge Associates (see here) supports the thesis that specialism leads to outperformance. We find that it is very rare to see an emerging manager attempt to execute a generalized approach with success. We also find when emerging managers extend into other areas beyond venture and private equity, such as Infrastructure and Real Assets, they focus on a specialized area within that larger universe. For example, instead of managing a portfolio of wind and solar farms, emerging managers might focus on investing in technologies that make renewable energy available to the masses.

• Psyche: How we think has a great impact on our personal drive. Our thinking patterns are subsequently triggered by both internal and external factors. In the Rise of the Super Human, Steven Kotler suggests people that have clear goals take a different view of risk/sense of danger/fear, and possess a high skill to challenge ratio. Both of these factors push them to perform exceptionally well. How does this apply to emerging managers? Individuals who strike out on their own to address untapped opportunity are usually self-driven and show a positive response to internal and external factors. Afterall, there is much at stake for them.

Specialism, be it across the size spectrum, region and/or sector spectrum does reward the investor. Psyche, although difficult to measure, becomes an artful discovery. Psyche is discovered as we look closer at the individual and go beyond what is written on paper in presentations. We consider what they do, what they say, and their activity tempo and rhythm.

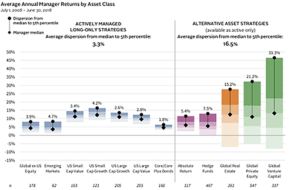

Manager selection does have an impact on overall fund performance. Cavagnaro et al, 2018 [6] show statistical evidential support that lends to the conclusion that variation in manager selection skill is an important driver of institutional investor returns. Harris et al, 2013 [7] shows managers tend to stay in their dominated quartile in subsequent funds whilst Cambridge Associates in a 2018 analysis reveal existence of dispersion in private assets (even greater in Venture than in others), which places a greater importance on manager selection.

We have summarized the attractiveness of managers into a descriptive and dynamic model that combines quantitative and qualitative data. One more qualitative factor we consider is a manager’s “Kadence.” To us, Kadence highlights the investment behaviour of the manager. It attempts to gauge the probability of the individual / manager achieving their stated returns or diverging from previous activity and anticipates whether the manager will repeat previous performance. Although at its infancy, we believe that this insight could grow into an effective tool for manager selection and monitoring.

Challenges for Emerging Manager Allocations

Despite emerging managers’ abilities to outperform their mainstream peers, allocation to emerging managers is a nascent activity for allocators. Allocators are challenged by small check size deployments relative to the work done by underwriting an emerging manager. I argue that undertaking investment due diligence for emerging managers should be equal to that of mainstream private asset managers, especially if evidence shows individuals drive private asset performance. Deal level analysis as opposed to fund level analysis has been shown to have more performance explanatory power in private equity performance. In instances where fund iterations are younger than two fund vintages, we argue for a combination, and perhaps, a higher weighting to deal-level analysis.

Operational set ups have usually created hindering blocks as well, but the growth of outsourced solutions has helped smaller organizations overcome many internal operational issues. Suffice it to say that we find those that are either plugged in to a platform where support is extended by a lateral provider - as opposed to those that attempt to conduct operational activities on their own with limited resources - are usually preferred.

Lastly, scalability can be a challenge for larger allocators. For larger allocators seeking access to smaller and emerging managers, their allocations should be rightsized in the portfolio. As a satellite is to a core in a portfolio, so is the emerging manager allocation to the main private markets. During market dislocations where systemic shocks create more opportunities for certain sectors, such as where we are now, the ‘satellite’ (i.e., the emerging managers’ allocations) will play a much larger role. Ultimately for access at the right time, relationship building with emerging managers and their capital fulfilment representatives needs to be a continual process.

Conclusion

In conclusion, when we look at private markets and the prospective additive benefits to a portfolio, we must look beyond the headlines of fund number and firm establishment. Instead, our top priority is to seek which managers that generate alpha. To us, what really matters are the people involved and whether said people have the relevant expertise and staying-power to execute. For allocators, implementing an emerging manager program requires an active relationship, with capital fulfilment representatives available to assist in reviewing the marketplace, and identify those managers who are typically under the radar.

Citations:

[1] Private Equity Performance: What do we know? Robert S Harris, Tim Jenkinson, Steven N. Kaplan, The Journal of Finance, Vol 69, Issue 5, October 2014

[2] Ewens, Michael and Matthew Rhodes-Kropf, 2015, Is a VC Partnership Greater Than the Sum of Its Partners?, The Journal of Finance 70, 1081-1113

[3] Whom to follow: Individual Manager Performance and Persistence in Private Equity Investments, Reiner Braun, Nils Dorau, Tim Jenkinson, Daniel Urban, Oct 2019

[4] Braun, Dorau, Jenkinson. Whom to Follow: Individual Manager Performance and Persistence in Private Equity Investments

[5] Emerging Manager Programs: A Best Practices Overview, June 2011

[6] Measuring Institutional Investors’ Skill at Making Private Equity Investments, Daniel R Cavagnaro, Berk A Sensoy, Yingdi Wang, Michael S Weisbach, Dice Center WP 2016 -14 Fisher College of Business WP 2016 03 14, April 17 2018

[7] Has Persistence Persisted in Private Equity? Evidence from Buyout and Venture Capital Funds. Robert S Harris, Tim Jenkinson, Steven N Kaplan and Ruediger Stucke, April 2013