By Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM, FDP, Director, Global Content Development at CAIA Association

Steve Wozniak: “You can't write code... you're not an engineer... you're not a designer... you can't put a hammer to a nail […] So how come ten times in a day, I read Steve Jobs is a genius? What do you do?”

Steve Jobs: “I play the orchestra. And you’re a good musician, you sit right there and you’re the best in your row.”

Steve Jobs was a polarizing figure, so don’t view this quote as me giving him an award for personality. However, I will give Mr. Jobs credit where it’s due; he surrounded himself with brilliant people who were very good at what they did and ultimately fostered one of the most successful companies in recent history. There are many parallels between this story, organizational structure, and how our investment profession thinks about investing today. Like many professions, investment management also tends to favor and incentivize deep subject matter expertise and technical ability over systems-level thinking and the horizontal bar of T-shaped skills. Often, the latter are written off and the term “generalist” is used as a derogatory term, rather than someone who understands multiple facets of industry, and something to aspire towards.

We’re missing the bigger picture. I’ve always been a person who likes to see the forest through the trees. I enjoy putting myself in a place where I’m able to create/embrace a narrative, see all angles of a situation (or a portfolio!), and proactively adjust in real-time. It’s where I tend to thrive. But, as investment professionals, we are rarely trained to think this way. Many academic institutions focus on asset class specialization, typically on publicly traded equities, but post-undergrad I quickly learned how much I preferred thinking across the entire portfolio, and really focusing on what counts – my beta exposures. I loved thinking about what exposures I wanted to lean into and lean away from, how different asset classes played defense and offense, and how the underlying managers interacted with one another. Most importantly, I loved seeing how the total objective was being achieved through my decisions of capital allocation. I was playing the orchestra, and I had the opportunity to select the best musicians.

What does it really mean to “think like an allocator?” An allocator is not a job title, it’s a mental framework. To think like an allocator is to acknowledge that a healthy portfolio consists of different players that take on different roles to help achieve the common objective. Like Apple needs engineers, coders, and marketers, an allocator needs all of the tools at their disposal and decisions cannot be made in silos of isolation, such as one asset class. It means thinking through all of the risks, not just in terms of statistical measures, like standard deviation, but illiquidity risk, manager risk, and, importantly, shortfall risk. It means thinking through ESG factors, and how those factors influence cash flow distributions and mark-to-market. Finally, it means thinking through a mosaic of allocation techniques, acknowledging that singular frameworks come in and out of favor.

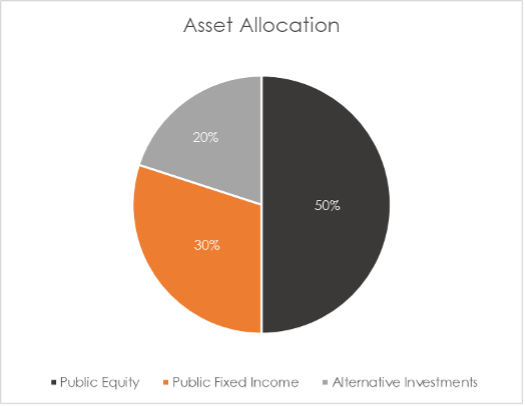

Everything is an alternative. While pie charts are an important narrative device, as a mental framework they often handcuff us into making suboptimal portfolio decisions. The moment we give ourselves a quota for a particular asset class is the moment we have lost the point of allocating capital in the first place.

Source: Author’s calculations. For illustrative purposes only.

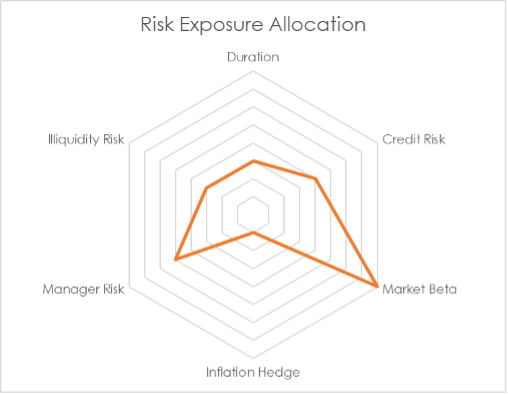

At first glance, the asset allocation above makes intuitive sense, but at a further glance, we realize that each of these categories covers multiple styles, exposures, and risks. Not to mention the 20% of “alternative investments” covers a lot of things that don’t even relate to each other (private infrastructure and hedge funds in one category?). Further, separating any of these from the rest of the portfolio does a disservice to explaining the true exposures of allocation. Technically, everything is an alternative investment – after all, isn’t investing all about opportunity cost? Instead of thinking about dollar allocations, I would encourage us all to think a bit more about underlying risk drivers. Sure, we may end up with the same pie chart at the end of the exercise, but, as I have written about before, an allocation should merely be the byproduct of the end objective. Perhaps this image is more appropriate:

Source: Author’s calculations. For illustrative purposes only.

This requires us to think about asset classes a bit differently too. Sometimes, I think we get caught up in the vehicle of an investment (ETF, mutual fund, LP, etc.) that we forget that many of these strategies have similar underlying economic drivers and risk characteristics. Public equity and private equity both represent equity stakes in a company, so why do we treat them as separate things in a total portfolio context? Sure, you are accessing different areas of the market at different stages of development, so there will be many things that differentiate them, but let’s not forget the most basic elements of both.

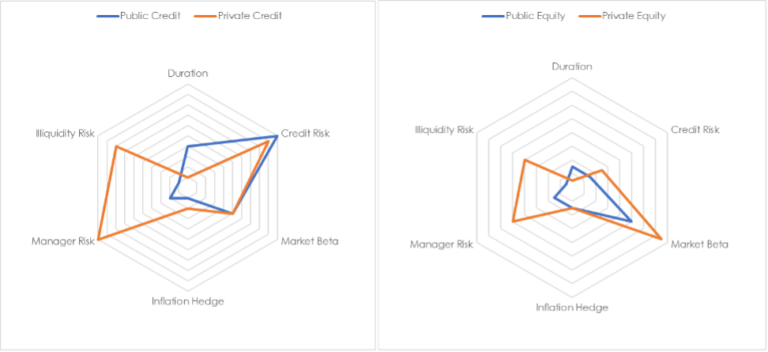

The two charts below present a simple visual framework at the asset class level, of which I believe better articulates the underlying risk drivers. For illustrative purposes, I compare the risks of public and private capital. In my illustration, you will notice that there is a level of overlap in underlying risk drivers, but private capital introduces clearly two additional dimensions of risk – illiquidity and manager risk. For those who are a fan of arithmetic, perhaps: Manager Risk + Illiquidity Risk = Complexity Premium.

Source: Author’s calculations. For illustrative purposes only.

Think different, think like an allocator To be an allocator is to think differently about investing than a typical specialist investor. Of course, you still need your specialists to get the job done, but, to quote one of my favorite books of late, Range: How Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, by David Epstein: “Overspecialization can lead to collective tragedy even when every individual separately takes the most reasonable course of action.”

While Steve Jobs didn’t code, engineer, or build the physical computer, it was his role to make sense of all of it and make it make sense for others. More than anyone, he understood the objectives – build something the customer wants, even if they themselves don’t know it yet. Imagine if Apple had left things up to the engineer? It may have been the most fascinating and technically proficient widget, but would it have made sense to the end user? The due diligence process of a two-way communication stream, a give and take between instrumentalists who have perfected their craft. When the GP and LP speak the same language, it leads to a better conversation, and when the GP understands how the LP thinks about them in the context of a total portfolio, it leads to better outcomes. Sure, eventually you need specialists to focus on their niche, but at the end of the day, someone needs to play the orchestra…by thinking like an allocator.

Seek education, diversification of both your portfolio and people, and know your risk tolerance. Investing is for the long term.

Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM, FDP is Director of Global Content Development at CAIA Association. You can follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter.