By Winston Ma, CFA, Esq., Executive Director of Global Public Investment Funds Forum and Adjunct Professor at NYU School of Law

President Trump’s recent announcement of a U.S. sovereign wealth fund (SWF), potentially aimed at acquiring a controlling stake in TikTok, has fueled both expectations and controversies. On February 3rd he signed an executive order directing the Treasury and Commerce secretaries to establish a U.S. sovereign wealth fund, which could serve as an economic development tool and perhaps be used to buy TikTok. Under a “sell-or-ban” bill that was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in January, ByteDance (the TikTok app's Chinese parent company) was required to divest its interest in TikTok by January 19, 2025, or face a nationwide ban. A separate executive order from Trump granted the TikTok app a 75-day reprieve from the ban, creating more time for a potential TikTok deal. The U.S. SWF may serve as the government’s representative to be a major shareholder of TikTok, with Trump stating that he “would like the United States to have a 50% ownership position in a joint venture.”

Some background first. A sovereign wealth fund is a state-owned investment fund that manages a country’s financial assets, typically derived from surplus reserves, natural resource revenues, or trade surpluses. These funds are generally managed by a country's ministry of finance, a central bank, or a specialized government agency. The TikTok ownership proposal has raised eyebrows because it does not align with the common objectives of global SWFs, which typically include the following (some are already mentioned in the Trump Executive Order and related Fact Sheet):

Fiscal Stabilization: Mitigating economic volatility and smoothing government budget in times of commodity price fluctuations.

Savings for Future Generations: Building wealth reserves to sustain economic stability in the long term.

Economic Diversification: Reducing dependence on a single revenue source (for example, fossil fuels) by investing across various sectors.

However, it is not uncommon for a sovereign wealth fund’s objectives to include strategic investments in key industries. While it’s not yet clear what structure the proposed U.S. SWF would take, it could operate as a “strategic” fund to help deploy the administration’s policies – like the TikTok situation, as some global SWFs do. Take Germany’s Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), for example. KfW was founded in 1948 as part of the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of the German economy, and it has been an important instrument for the economic and financial reorganization of Germany post-WWII. In 2018, the German government blocked the State Grid Corporation of China from purchasing 20% of 50Hertz, a power grid operator in eastern Germany that provides electricity to over 18 million German customers. In the 50Hertz deal, Germany exercised its powers under its newly revised foreign investment review law and used Germany’s KfW to acquire a critical stake of the target company to satisfy the related transaction requirements.

The background of the 50Hertz controversy was that Germany tightened scrutiny for foreign investments by formally amending foreign investment rules for critical sectors. The plan would expand “critical industries” to sectors including artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, biotechnology, and quantum technology, and would require disclosures for any purchases over 10% of companies in those areas. Meanwhile, for other sectors that had previously been identified and regulated as “critical infrastructure,” including energy, telecommunications, defense, and water, the percentage threshold that triggers government review was lowered from 25% to 10%.

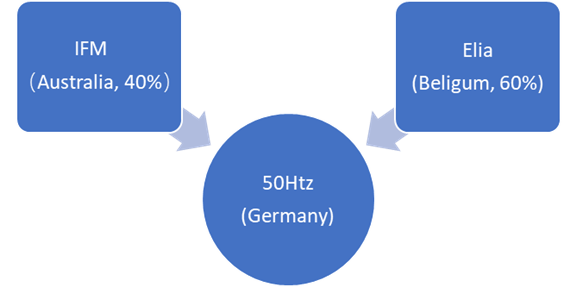

Figure 1: Ownership of 50Hertz before IFM Stake Sale

The 50Hertz ownership seller was IFM, an Australian firm owned by and managing infrastructure investments for its country’s superannuation funds. Before the German government intervened, IFM was looking to unload its 40% interest in 50Hertz. (See Figure 1.) Elia, a Belgian transmission system company and then owner of 60% of 50Hertz, exercised its right of first refusal for 20% of 50Hertz, leaving State Grid in talks to acquire the 20% still owned by IFM.

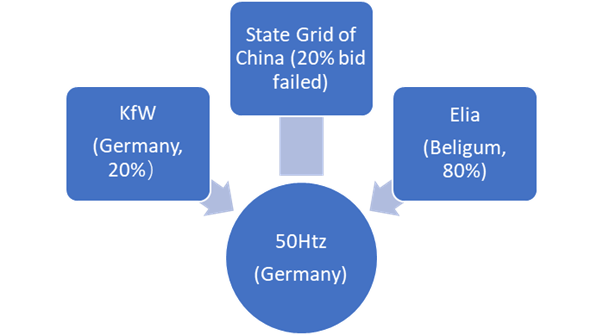

The German government voiced concerns, invoking the “critical infrastructure” status of the company that provides electricity for Berlin, among other places. The interesting twist was that, in this case, Germany was able to freeze out State Grid without explicitly vetoing the deal. This was because Elia, the 50Hertz majority shareholder, had the right of first refusal. At the direction of the German economics ministry, Elia exercised the option (IFM no longer being a shareholder), after which it immediately sold the stake to KfW (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Ownership of 50Htz after IFM Stake Sale

KfW clearly serves as Germany’s SWF, because it makes investments on behalf of the Federal Government from time to time, where “the shareholder rights are exercised by the German Federal Government,” as in the case of 50Hertz and other investments. Interestingly, the German KfW has also taken strategic stakes in German tech companies where U.S. capital was involved. On June 15, 2020, KfW moved to preempt a U.S. deal by acquiring a 23% stake in Cure-Vac, a German company with a promising coronavirus vaccine, after the Trump administration was rumored to be interested in acquiring the company.

Against the backdrop of global SWFs’ practices, it’s not surprising that the Trump administration's potential SWF investment strategy could include acquiring significant assets or strategic stakes, such as the purchase of TikTok interests, which may be a cleaner solution to give the U.S. a stake in the company without banning it outright. Of course, the potential U.S. SWF’s suitability as a deal platform is no guarantee that a TikTok deal with Chinese parties would be successful. The U.S. SWF has no details yet (including where, exactly, the first batch of capital will come from). There will also be many approval hurdles on the Chinese side, including corporate level shareholder’s approval (which includes the “golden shares of the state”), the export approval relating to TikTok’s advanced AI, and the unprecedented Chinese national security review of a deal involving a U.S. sovereign investor. That’s because it’s common practice that potential transactions through a foreign SWF require rigorous evaluation of its national security implications by the host country – just like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which screens foreign direct investment into U.S. companies for national security risks. The CFIUS has reviewed and challenged many acquisitions involving foreign capital, including TikTok itself.

In 2017, Chinese tech firm ByteDance paid $1 billion for the startup musical.ly in the U.S. – the origin of the now viral social video app TikTok. CFIUS approval was not sought at the time, leaving the deal vulnerable to a subsequent divestment order from the agency. In other words, TikTok’s forced sale today originated from its skipped CFIUS review years ago. Now the table is turned: if the TikTok split-up becomes the first deal of the U.S. SWF, it would also be the first deal to seek transaction approval by China’s foreign investment screening regimes.

In summary, the new U.S. SWF could be the perfect platform for a TikTok deal. The idea of using a state-backed fund to buy half of TikTok is unconventional – but surprisingly in line with global market practice. If the TikTok split-up materializes, the U.S. SWF’s impact could soon be felt in many sectors.

About the Contributor

Winston Ma, CFA & Esq., is an investor, attorney, author, and adjunct professor in the global AI-digital economy. He is a partner of Dragon Global, an AI-focused family office (founding member: Dragon.AI), and he is also the Executive Director of Global Public Investment Funds Forum and an Adjunct Professor (on Sovereign Investors) at New York University (NYU) School of Law. Most recently for 10 years, he was Managing Director and Head of North America Office for China Investment Corporation (CIC), China’s sovereign wealth fund. Prior to that, Mr. Ma served as the deputy head of equity capital markets at Barclays Capital, a vice president at J.P. Morgan investment banking, and a corporate lawyer at Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP.

Learn more about CAIA Association and how to become part of a professional network that is shaping the future of investing, by visiting https://caia.org/